I just want to wish the dads out there — all the different kinds of dads! — a very happy Father’s Day. I know some people will say the holiday is contrived or, weirdly, issue theological judgments (“read the room” appears to be the only appropriate response I have), but small occasions to remember the hard work people do are precious. Are those occasions enough? Almost always, no. Of course not.

But does perfect have to be the enemy of the good?

If America is going through hard times—and America is—that has a lot to do with the decisions people in power made. What they’ve chosen to prioritize. Who they’ve chosen to prioritize. But maybe some of that has to do with all of us, too. With what we’ve chosen to pay attention to — and put up with. We live in a society that puts the human needs of human beings all too often at the end of the list.

What can we do to take that back?

For one, on this Father’s Day, I invite each and all of us to reflect on our own priorities. What are we doing with our time? With our money? With our knowledge? With our faith?

I’m sharing the below note because you should read it. You don’t have to agree with it. But you should read it. Is Islam meant to make us feel better?

Or is Islam meant to help us become better?

Yesterday, we had the first middle school halaqa as I’ve reinvented it, following on insights I’ve learned (sometimes the hard way) from the AP Halaqa.

I had six boys. Five are South Asian. One is North African. I handed them each their copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Before we started, I explained to these eighth graders what the Socratic method is. I told them that, over the next year, we are going to interrogate ourselves and our faith and our priorities while reading and engaging Malcolm X’s autobiography (may God give him paradise).

I used overly abstruse words, like “abstruse.” I used words I’m entirely sure they don’t know the definition of. I listened as they read from the first two pages. That’s all we did: Two pages. A few paragraphs. Some of them, it’s clear, almost never read. They not only can’t read fluently, but they struggle to understand what they’re reading. Priorities. Our own, as parents, perhaps? Our educational system?

America has money for another country’s wars. But we seem to find it hard to find money for our future. What’ll give us the strength to ask for better outcomes?

I told them about Malcolm X’s reaction to seeing dark-skinned pilots on his flights in the Middle East; he’d never imagined seeing that. He was proud, moved, inspired. I told them that happened within their grandparents’ lifetimes. That the world they inhabited wasn’t just novel and new, from the perspective of much of recent history, but unlikely to endure unless and unless we commit to maintaining it.

But before we can commit to maintaining anything, we have to know what it is, where it comes from, its complexity and depth; they asked about the Nation of Islam and I gave them a complicated answer, one that refused simple binaries. Not least because they are old enough to know the world is not that crude but that, as Muslims, our conversations are not abstract debates.

If faith is about acting in the world, on ourselves and for others, then responses that reduce the world to bullet points or talking points are unjust, absurd, and even arrogant; they are dangerous and self-defeating. Once Atatürk heard of a poem ‘Allama Iqbal had written, that was critical of him; Atatürk allegedly laughed in response, saying, “when Iqbal has liberated India, then we can talk.”

What is it to be a man—to put others down? Or to lift others up? To pursue wealth and privilege (which, given the way the world is going, might not last us very long) or to pursue generosity and beauty? We talked about the Reverend Earl Little and about his courage. We talked about who Malcolm was writing for. Did they understand that he was writing for them, too?

That very likely, none of us would be in that room, or in this country, if not for people like him and the civil rights movement and now, what we see, it is not hard to believe that those who never accepted these changes… they want to roll them back.

I told them they’d have to read the first chapter by next week. (If they don’t, there will be consequences, and they will be boring.) Is that enough? Watching yet another war in the Middle East, the political violence in Minnesota, the hundreds of thousands of Americans who came out to insist that we must be a democracy, I am reminded of the most important lesson this Father’s Day, at least as I see it.

Yes, we are all tired. Yes, we probably all want a vacation. Definitely, we deserve and need vacations.

But if we are exhausted, it is because we refuse to look away, turn away, or pretend that everything is fine. What is it to be a grown-up? To know that the world matters. That seriousness and responsibility are called for. That we matter.

That although we should and have to and want to make time to unwind, there’s always work to be done. I woke up at fajr and heard someone talking. I was confused: Who’s up at this time? It was our youngest. He was reciting Qur’an in his room. I knocked gently and asked him if he was going to stay up or go back to sleep. He said he was up; he’d slept early. So I asked if he wanted to join me at the gym.

On the drive, we joked about Mission: Impossible IV — we’d been watching the night before — and, in true IMF style, like a bunch of cross-generational Ethan Hunts, we showed up at the gym before it was open. So we watched news on my phone, went to workout for an hour, hit up a breakfast spot for some protein rich replenishment, found cheap gas, went to Kroger, and made it home before anyone was up.

Except the cats. The cats are always awake.

Is that enough? Are any of us, ever, enough? I don’t know. But if you ask that question. If you’re trying. If you believe you might be wrong. If you know there’s always lessons to be learned from others around us. If you can spare ten minutes to read, like Brother Malcolm did, if you know you’ve got a purpose in this life, and that purpose is good, then good on you.

May God bless you.

May God bless each and all of us.

May He give strength to us, protect our families and communities, look after us, and look after those who come after us. To help us keep going, when the world is heavy, when our hearts hurt, when our bodies creak and whine and groan.

The first episode of our new podcast, Avenue M, features Richard Reeves, talking about the crisis that’s facing many men. The date wasn’t unintentional. We are two men, Christian and Muslim, Midwesterners, middle-aged, men of faith, who hope we’re in our middle age, talking to remarkable men doing remarkable things. As for that first episode? Well, it’s not surprising how we’re starting.

But, and I’m not just saying this, we’ve got some absolutely incredible guests for the weeks ahead too.

I promise I’m not just saying that.

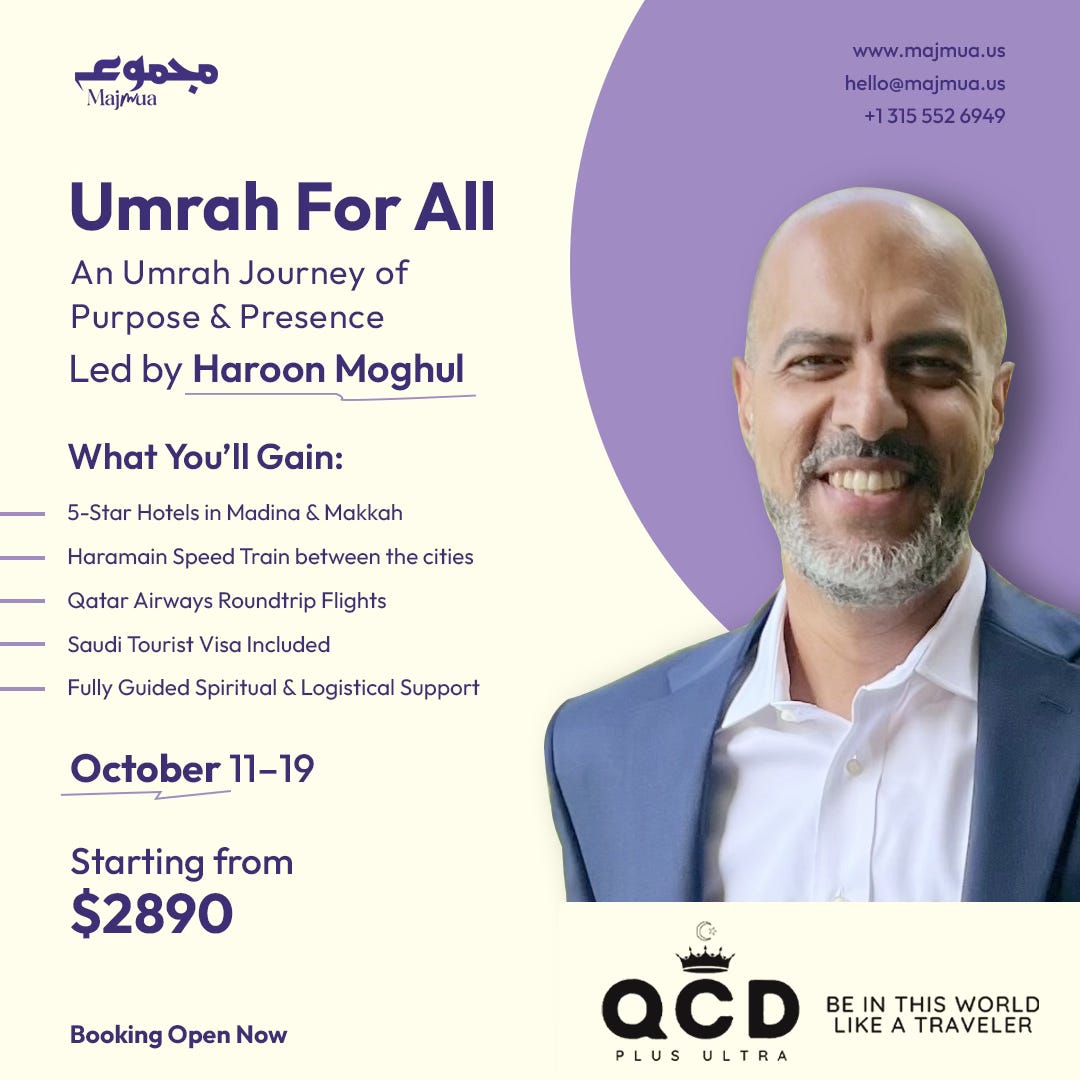

An Umrah For All of Us

And if these halaqas intrigue and excite you, well, there’s a chance to learn more: This October 11 - 19, I’m leading an ‘umrah trip that’ll bring my vision to a select forty-five guests (here’s how to sign-up). I might just invite us all to read The Autobiography of Malcolm X again. If you haven’t ever read The Autobiography, though, well, consider this your first assignment.

We can’t expect the kids to learn and not model that ourselves, can we? If you appreciate experiences that make us work, that ask us to push ourselves, and that invite us to do so with others who share our goals, who can laugh and smile, who know there’s priorities and possibilities, who want better and want to build that better, this trip might just be for you. Our podcast, too.

And definitely this Substack.

Lol, I had to look it up.

abstruse

Difficult to understand; obscure.